Solar Household Systems in Malawi

Over the last 7-8 years, basic solar lighting products have enabled Malawians, particularly those in rural regions, to transition away from kerosene lamps and torches, to brighter and more cost-effective lighting. While the statistics on adoption are sketchy, it is estimated that up to 2 million Malawians have benefitted from these small-scale products. However, while affordable, these entry level products are unable to cater to the growing energy needs of populations in Malawi. Apart from the need for high quality lighting throughout their homes, the vast majority of households in Malawi own at least one mobile phone, thus phone charging has become a vital energy service. Understandably, households also desire to power appliances that they see as part and parcel of “the good life”, this includes sound systems, televisions, fridges and electric stoves. Many own such appliances but have no means to power them. So while solar lanterns have played a useful role in providing Malawian households with an alternative to kerosene lamps and torches, they are unable to cater to the ever-growing energy needs of Malawians. This is where solar household systems come in…

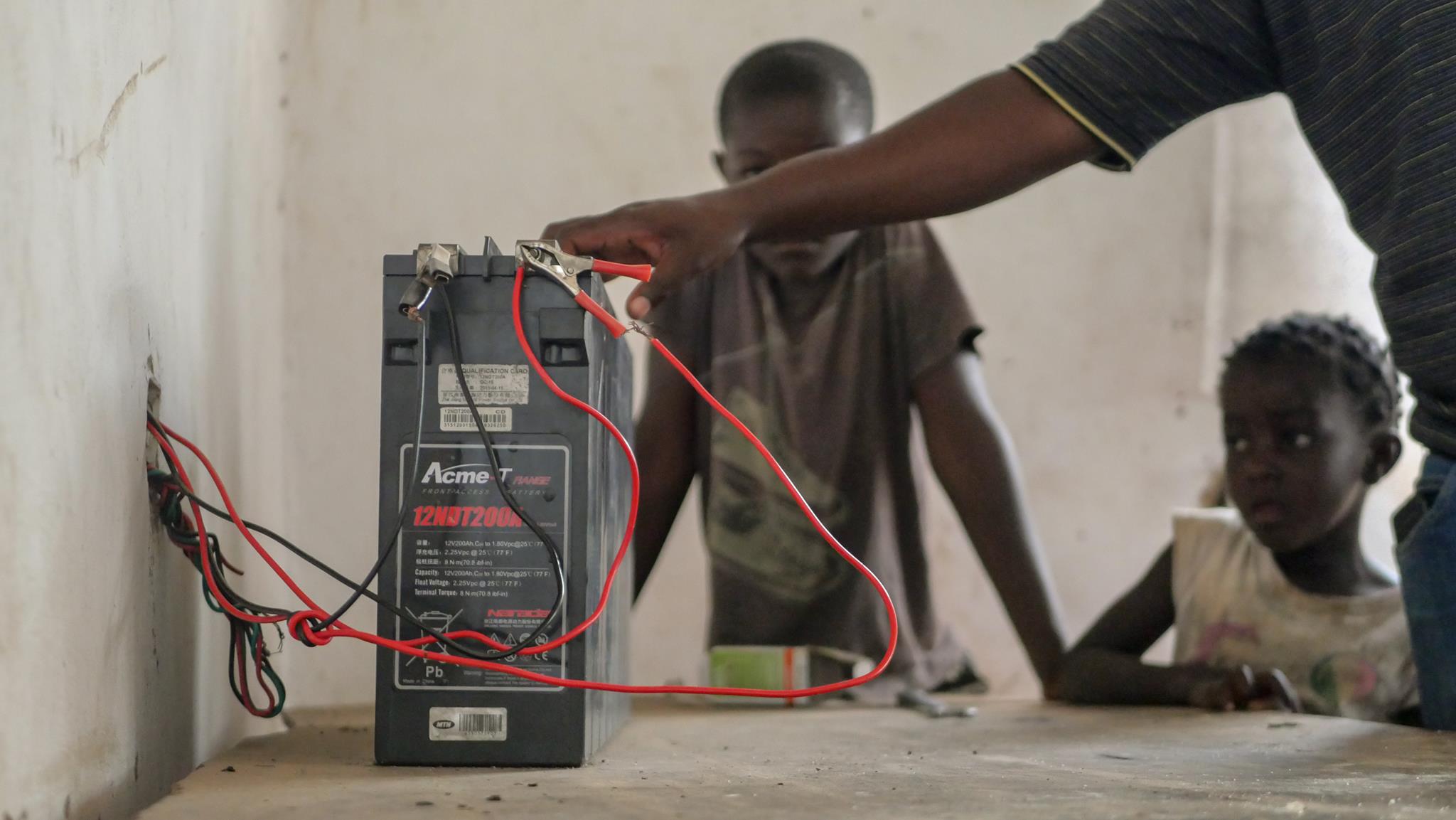

Shousehold systems (SHS) typically involve a combination of a solar panel, a battery (to store power) and LED lights. Depending on whether the systems use alternate (which we use in our homes) or direct current, the system might also require an inverter (to convert electricity to the right voltage). There is a wide spectrum of SHS, ranging from basic systems that can power multiple LED bulbs and charge phones, to those that can power fridges and televisions. Given the slow expansion of the grid, and the high frequency of blackouts, SHS are widely seen as a very attractive means through which households can either replace or supplement grid access. The following excerpt form a household interview speaks to this:

"Bright: We have noticed that you have both systems - a solar system and ESCOM (grid access) In terms of use, why haven't you completely switched to using ESCOM?

Hastings: I haven't switched completely to ESCOM because of one major reason, our ESCOM power capability is not reliable. We expect blackouts nearly every day...except this month of January because I heard that the Malawi Govt sourced power of 30MW from the Republic of Zambia. Yeah...but blackouts were the order of the day in Malawi. So there's no way ...at any point in time I should say that I have no plans to completely switch from solar to electricity power. No. Our electricity is not reliable"

While SHS is a very attractive alternative to grid-based electricity, affordability has been a huge barrier to adoption. This has been eased by global reductions in the costs of panels and batteries, as well as the advent of financial innovations such as pay-as-you-go (PAYG). As the name would suggest, the latter allows households to pay for these systems incrementally (typically 6-21 months), thereby reducing upfront cost as a barrier to adoption. From an energy justice perspective, it could be argued that this innovation is furthering distirbutive justice as it allows for a greater number of households to afford a solar system.

While millions of these pay-as-you-go solar systems (PAYG SHS) have been sold in East Africa, this technolgoy is still at a nascent stage in Malawi. In fact, I am a co-founder of a PAYG Solar company in Malawi called Zuwa Energy, one of the first to offer PAYG SHS in Malawi. To be clear though, my research is concerned with energy justice issues that are relevant to the SHS industry as a whole. As I’ll elaborate on soon, there are a host of benefits and challenges that the industry has to contend with.